There is no American music that doesn’t have Black roots. From country-western, which draws upon banjo music from Africa, to rock ‘n’ roll, begun by a Black woman playing electric guitar in 1938, American music can’t be separated out from its rich history of diversity and experimentation.

Every artist transforms his or her medium simply by working in it, and it so follows that every musician changes the art form slightly just by creating and performing songs. But throughout American history, there are examples of artists who have been so transformative as to change musical genres themselves. Other times, artists unwittingly create new genres—whether Fela Kuti with Afrobeat, Frankie Knuckles with house music, or Fats Domino with ska.

To take a closer look at how Black musicians shaped American music, Stacker pored through historical documents, recordings, Billboard charts, and studied similarities in various musical acts over time to determine 41 artists music wouldn’t be the same without. Paring the list down to just 41 was a challenge (the gallery could easily include hundreds)—so there are certainly icons missing, including powerhouses like Lightnin’ Hopkins, Wilson Pickett, Mary Wells, Roberta Flack, Tina Turner, and Gloria Gaynor—each of whom has made significant contributions to music in his or her own right. To help narrow the field, we focused on artists whom scholars can definitively conclude altered the musical landscape in some dramatic fashion. Artists highlighted in this gallery changed the course of music by doing something entirely new with it rather than simply building upon the legends who came before (although those in this list certainly did that, as well).

Beyond musicianship, many Black artists throughout history also saddled additional burdens and bravery by challenging the status quo (often against all odds) and pushing for equity. From Marian Anderson, who inspired Eleanor Roosevelt to drop out of the Daughters of the American Revolution when the group wouldn’t allow Anderson to sing in front of an integrated audience (Anderson ended up singing in front of 75,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial and was the first Black person to perform with the Metropolitan Opera in New York), to Ray Charles, who refused to perform for an all-white audience in Georgia, there is example after example of musical icons who used their platforms to make incremental changes driving toward a more perfect union.

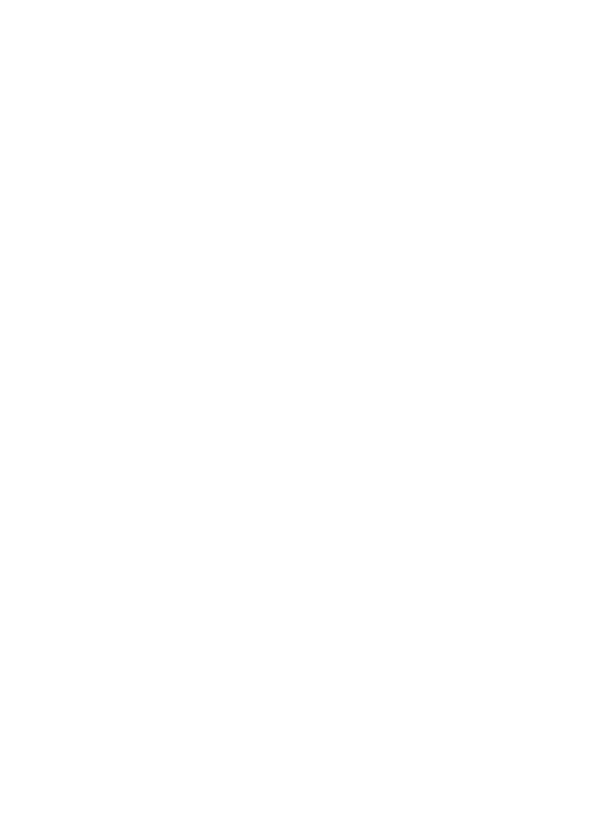

1. Scott Joplin

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Maple Leaf Rag” (1899)

– Who he inspired: Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, Fats WallerScott Joplin grew up along the borders of Texas and Arkansas in a musical family. The second of seven children, his father was a former slave who worked on the railroads for a living and played violin; his mother was a house cleaner, singer, and banjo player. By the time he was a teenager, he was making a living as a music instructor and piano player, traveling as far as Syracuse, New York, for gigs and playing in various groups including the Queen City Cornet Band and Texas Medley Quartette. He eventually settled in Sedalia, Missouri, for several years. There, he got jobs at two social clubs for Black men that were founded in 1898: the Black 400 and Maple Leaf clubs.

He collaborated with local musicians to write ragtime music, a style of syncopated beats and accents popular at the time that would form the foundations of the Harlem stride style of piano playing and the forthcoming jazz era. Ragtime drew on songs from minstrel shows, cakewalk dance rhythms, and Black banjo music. Joplin published his most famous work, “Maple Leaf Rag,” in 1899 and thereby cemented his legacy as the King of Ragtime.

Joplin by 1916 was suffering from advanced stages of syphilis, which historians surmise he contracted decades earlier. He was hospitalized in 1917, moved to a mental institution, and died April 1 of that year.

2. Louis Armstrong

Bettmann // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “West End Blues” (1928)

– Who he inspired: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Prima, Tom WaitsLouis Armstrong goes down in history as what scholars call the “first great jazz soloist” and quite possibly the single most influential players in American music. After overcoming the extreme poverty he was born into, Armstrong’s musical contributions during the Harlem Renaissance can’t be overstated: He was the first to bring the concept of an improv soloist (in his case, as an accomplished trumpeter), front and center.

Louis Armstrong, along with his Hot Five and Hot Seven groups, made a series of recordings between 1925 and 1928 heralded today as the most transformative influence of jazz music. Famed music critic Dan Morgenstern once said, “There is not a single musician playing in the jazz tradition who does not make daily use, knowingly or unknowingly, of something invented by Louis Armstrong.”

3. Bessie Smith

Anthony Barboza // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” (1929)

– Who she inspired: Billie HolidayAnyone who sang (or listened to) the blues since Bessie Smith has been subjected to her influence. She was known for filling a room with her voice sans microphone and depth of what she sang about: everyday worries for everyday people, with a confidence and bravado that could stop you in your tracks. Her relatively short, 10-year recording career nevertheless managed to profoundly influence the totality of American music in the 20th century.

4. Robert Johnson

Delta Haze Corporation // Wikimedia Commons

– Essential listening: “Sweet Home Chicago” (1936)

– Who he inspired: Allman Brothers, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, the Rolling StonesThe legend goes that Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at Mississippi crossroads to gain his guitar-playing prowess that seemed to show up overnight. Known as the first bluesman of modern American music (specifically the Delta blues style), Johnson recorded tunes in 1936 and 1937 in room 414 of the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, Texas, which was set up as a temporary recording studio. Those tracks were finally properly compiled as “The Complete Recordings” in 1990. A member of the “27 club,” Johnson’s death (either by murder, pneumonia, or syphilis) is shrouded in as much mystery as his life.

5. Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Tony Evans/Timelapse Library Ltd. // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Rock Me” (1938) (bonus video: “Didn’t It Rain”)

– Who she inspired: Jerry Lee Lewis, Jimi Hendrix, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Isaac Hayes, Aretha Franklin, Chuck BerryBefore there was Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, or Jimi Hendrix, there was Sister Rosetta Tharpe inventing rock ‘n’ roll with her electric guitar. Tharpe had a good grasp on guitar-playing by age 6 and began playing in churches and on street corners while her mother proselytized. The Godmother of rock ‘n’ roll bounced around—from Arkansas where she was born, to Chicago, and eventually to New York City—and ultimately got in at the legendary Cotton Club in Harlem where she was exposed to mass audiences. There, she became the first crossover gospel artist, performing worship songs as well as rock ‘n’ roll, which she was helping to birth. She’s the first to have used heavy distortion on her guitar, the first to have a gospel reach the R&B top 10 (“Strange Things Happening Every Day” in 1945), and, as a bisexual woman, a trailblazer for LGBTQ musicians.

She recorded her most influential song that most clearly lays the foundation for rock ‘n’ roll, “ Rock Me,” on Oct. 31, 1938—when Elvis was 3, Little Richard was 6, Chuck Berry was 12, and B.B. King was 13. When her guitar-playing was compared to that of man, Tharpe had a rebuttal ready: “Can’t no man play like me. I play better than a man.”

You can hear Tharpe’s “This Train” in Little Walter’s “My Babe;” see her eccentric movements in Elvis’ hips; and—lest you doubt her influence over greats like Chuck Berry, who once famously said he saw his career as “one long Sister Rosetta Tharpe impersonation”—see if the opening measures of “The Lord Followed Me” sound familiar.

6. Duke Ellington

Bettmann // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Mood Indigo” (1930)

– Who he inspired: Thelonious MonkDuke Ellington is synonymous with Harlem nightlife and big-band jazz, working alongside powerhouses like Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong to push jazz to the masses. Ellington had the uncanny ability to write commercially viable songs without surrendering his artistry. He drew inspiration from stride pianists James P. Johnson and Willie “The Lion” Smith, and managed to transform every facet of music he took part in—from composing and arranging to roles as pianist or bandleader. His ability to keep up with the times maintained his relevancy throughout his lifetime and ever since and secured him dozens of awards throughout his tenure, from 13 Grammys and a Pulitzer to the 1969 Medal of Freedom.

7. Billie Holiday

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Strange Fruit” (1939)

– Who she inspired: Paula West, Joey Arias, Joni MitchellA young Billie Holiday listened to 1920s Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong records on a Victrola at the brothel where she scrubbed floors. But instead of mimicking their vocals, Holiday had a different approach: a hushed, almost reluctant voice cloaked in suspense that was suited perfectly for new microphone technology in the 1930s that could amplify her sound. She was catapulted into the spotlight with her 1939 recording of “Strange Fruit,” a protest song about the lynchings of African Americans.

8. Louis Jordan

Bettmann // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Caldonia” (1945)

– Who he inspired: James Brown, Ray Charles, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Fats DominoLouis Jordan is celebrated for serving as a bridge between blues and jazz on one side, rock ‘n’ roll and R&B on the other—earning him the moniker “The King of R&B.” Behind-the-scenes, Jordan showed an uncanny ability to read changing musical tastes and a shifting music-production scene, as the American Federation of Musicians went on a two-year strike during Jordan’s extended stay with the Tympany Five in the Midwest. His rise coincided with confusion in the music industry as jukeboxes and radio playlists distorted income streams within the industry.

Jordan’s popularity spanned two decades from the ‘30s to the ‘50s and included duets with some of the time’s most major acts including Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, and Ella Fitzgerald. He spanned entire musical genres from big band to jump blues and earned roles in numerous promo film clips as well as feature-length films. He was a gifted player of the sax, piano, and clarinet, and was a major writer and co-writer of iconic songs throughout the 20th century including “ Let the Good Times Roll” and “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby.”

9. Thelonious Monk

David Redfern // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Straight, No Chaser” (1967)

– Who he inspired: Herbie Hancock, John ColtraneThelonious Monk—an early founder of bebop and modern jazz—is widely revered as one of the world’s greatest jazz pianists in history. Monk was largely inspired by stride piano, a style developed along the east coast (mainly in Harlem) in the 1930s and ‘40s whereby the left hand plays a four-beat pulse while the right hand keeps melody—a style initially popularized by ragtime musicians like Scott Joplin and used by musicians like Duke Ellington and James P. Johnson, who Monk counted among his biggest influences.

Monk played with various groups (and fellow heavyweights like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker) at Minton’s Playhouse, a jazz club in Harlem that served as an institution still standing today in which bebop and modern-day jazz were born. He began recording in 1944, but didn’t have commercial success until 1956’s “Brilliant Corners.” He is among the most-covered of all jazz musicians, and many of his songs have become jazz standards—from “Straight, No Chaser” to “Round Midnight.”

10. Nat King Cole

Imagno // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Unforgettable” (1952)

– Who he inspired: Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Michael JacksonNat King Cole was born in Birmingham, Alabama. His father was a respected pastor of the First Baptist Church, who moved the family to Chicago in 1921 as part of a large South-North migration for African Americans seeking more opportunity. Cole’s mother, a choir director at the church, began teaching her son to play piano by ear when he was just 4 years old.

Cole went on to defy racist notions to become the first Black man to perform romantic music for white people. He was also the first Black man to host a nationally syndicated TV show, “The Nat King Cole Show,” which premiered in 1956 and was canceled in 1957 due to lack of sponsorship. On the final episode, Cole performed “The Party’s Over.” Over his long career, Cole’s sound evolved from small-group jazz to pop singing sensation in the easy-listening genre—and his inroads in television would go on to inspire shows like “Arsenio Hall” decades later.

11. Ella Fitzgerald

Paul Natkin // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Air Mail Special” (1957)

– Who she inspired: Adele, Lady Gaga, Lana Del ReyElla Fitzgerald carried the distinction of being the most famous woman jazz singer in the United States for more than 50 years. She sold more than 40 million albums, won 13 Grammys, was awarded the National Medal of the Arts by President Ronald Reagan, and will forever be remembered as one of the greatest scat singers in history. Her fingerprints are all over modern-day pop stars, but Fitzgerald—who drew on be-bop influences like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and recorded more than 200 albums throughout her life—has further provided inspiration to countless people for her perseverance in overcoming life’s obstacles from poverty and racism to grief and hardship.

12. Etta James

Andrew Putler// Getty Images

– Essential listening: “All I Could Do Was Cry” (1960)

– Who she inspired: Janis Joplin, The Rolling Stones, Tina TurnerEtta James transcended musical genres, living at various times within gospel, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, soul, and R&B throughout her stunning, decades-spanning career. She was discovered as a teenager by Johnny Otis and came out in 1955 with her first hit, “The Wallflower.” From there, her meteoric rise included classic hits like “At Last,” “Something’s Got a Hold On Me,” and “I’d Rather Go Blind.” James is revered for acting as a bridge from R&B to rock ‘n’ roll, and has been honored with numerous Grammys and Blues Music Awards, and an induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Blues Hall of Fame, and Grammy Hall of Fame.

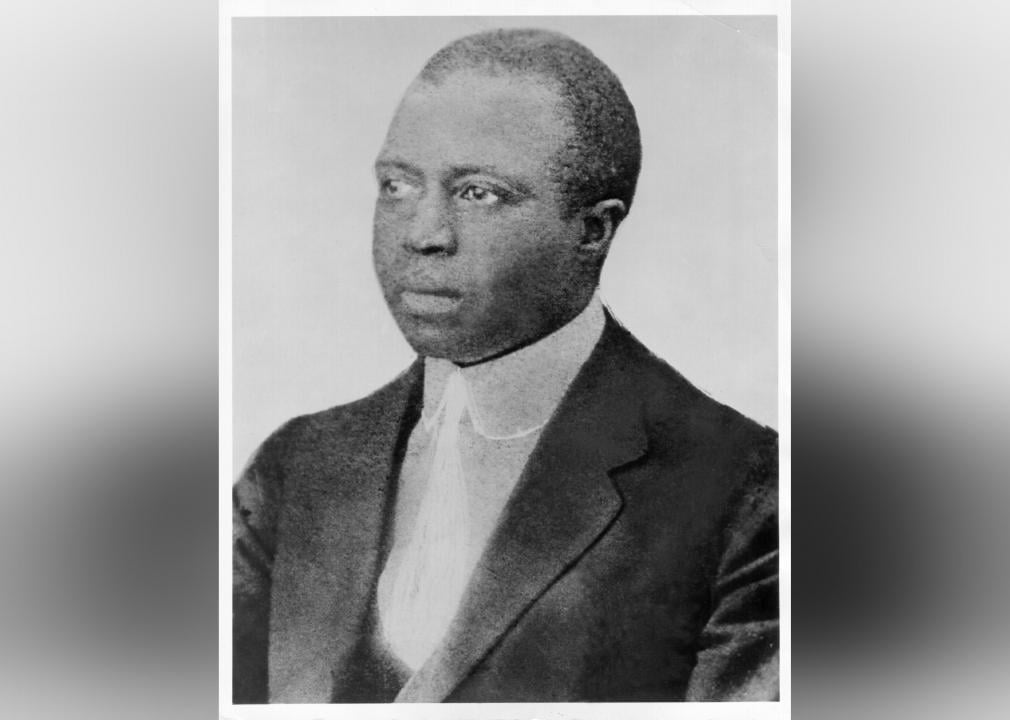

13. B.B. King

Estate Of Keith Morris // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “The Thrill Is Gone” (1969)

– Who he inspired: David Gilmour, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, Bonnie RaittWorld-famous for his insane blues licks and iconic Gibson guitars, B.B. King churned out 75 R&B hits between 1951 and 1992. His music pushed the boundaries of what blues could be, drawing on a changing musical landscape that brought in and built upon evolving sound in the industry. His influence as a rock and blues guitarist was virtually unsurpassed throughout the 1960s.

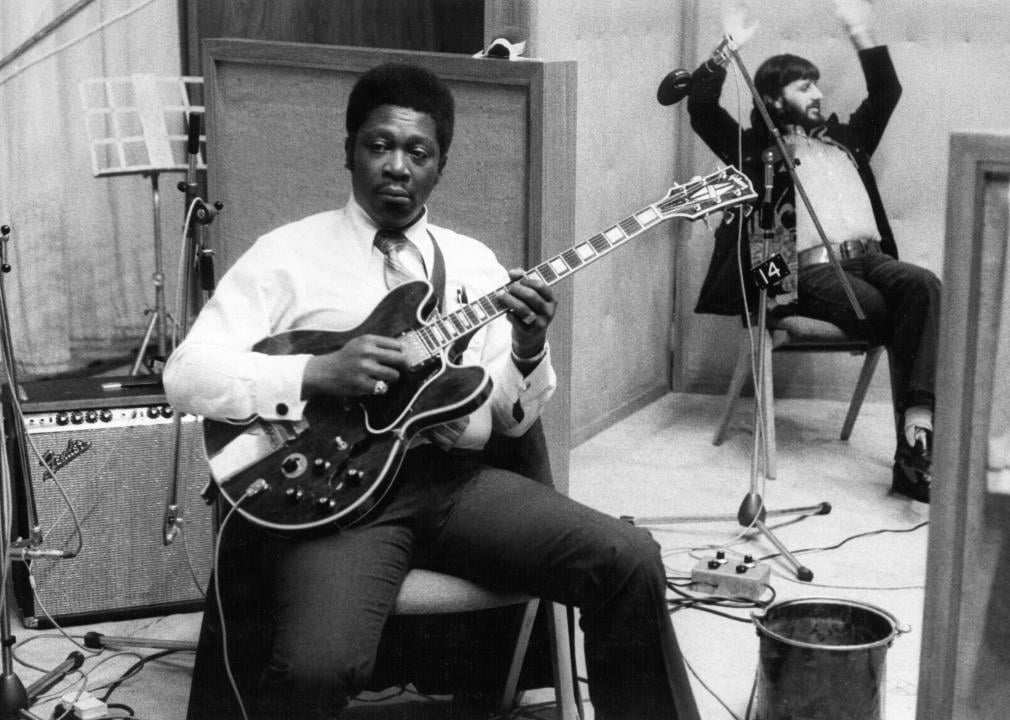

14. Chuck Berry

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Johnny B. Goode” (1958)

– Who he inspired: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Bruce SpringsteenA devoted student of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Chuck Berry brought R&B music into households across the United States and world. Quite possibly the most important early breakthrough rock ‘n’ roller, Berry had as good—or better—songwriting chops, melodic voice, and guitar skills as anyone in the industry at the time. No one could touch Berry throughout the latter half of the 1950s, and early 1960s, as he churned out hit after hit tracks like “Rock and Roll Music” (1957), “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” (1957), “Sweet Little Sixteen” (1958), and “Roll Over Beethoven” (1963).

Berry’s ascent came at the cost of him swallowing his perspectives on racial tensions of the time and editing song lyrics to make them more palpable for white audiences. In “Johnny B. Goode,” for example, Berry swapped the phrase “colored boy” for “country boy”—thereby changing the meaning from an autobiographical line to a more generalized anthem for America’s youth.

15. Ray Charles

Frans Schellekens // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “What’d I Say Parts 1 & 2” (1959)

– Who he inspired: Aretha Franklin, Billy Joel, Van Morrison, Elvis Presley, Stevie Wonder, Tina TurnerA blind piano virtuoso who could play blues, rock, jazz, and country Western (often multiple at the same time), Ray Charles was a true trailblazer for soul music, single-handedly shaping the genre with classics from “Hit the Road Jack” to “You Don’t Know Me” and injecting the genre into country-western music. His career spanned more than half a century with surreal accolades including 17 Grammys and having his rendition of “Georgia on My Mind” being named the official state song of Georgia.

16. Miles Davis

Jack Vartoogian // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “So What” (1959)

– Who he inspired: Duane Allman, Lester Bangs, Brian Eno, Tim Buckley, Rick James, Flea, PrinceMiles Davis’ albums did more than influence music: They changed it forever. From “Birth of the Cool” (1957), in which you can hear Davis leaving be-bop behind, to “Bitches Brew” (1970), the gold standard in jazz fusion, Davis demonstrates an uncanny ability to harness new sounds of the day and put them at the forefront of his music—oftentimes bringing the very musicians serving as those trailblazers into his bands. He innovated on every piece of music he wrote, took chances, and never grew complacent: No two of his albums are alike. The echoes of Davis’ impact can be felt throughout our culture.

17. Nina Simone

Tom Copi // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free” (1967)

– Who she inspired: Jay-Z, Lil Wayne, Tracy Chapman, Jeff Buckley, Mary J. Blige, Lauryn Hill, John Legend, David Bowie, Aretha FranklinWhile other Black artists of the time worked on the TV circuit, played nice with white audiences, and pursued commercial success in any way possible, Nina Simone refused to compromise.

As a child prodigy, Simone (born Eunice Kathleen Waymon) trained to become the first Black woman concert pianist. But a racially motivated rejection in 1951 from the Curtis Institute of Music sent Simone on another path entirely. Adopting a stage name to hide the fact she was playing what her minister mother considered devil’s music, Simone started playing piano—and soon enough singing—in an Atlantic City, New Jersey, bar.

Her songs often dealt with issues of the day no one else would touch—from “Four Woman,” about a Black prostitute, activist, daughter of slaves, and interracial woman to “Mississippi God Damn,” about the murder of Medgar Evers, she was outspoken and unafraid of backlash to her honesty. In so doing, she laid the groundwork for future hip-hop artists, civil rights activists, and Black musicians.

18. Fats Domino

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Ain’t That A Shame” (1955)

– Who he inspired: Elvis Presley, Bob MarleyIn addition to his well-earned moniker as the “Godfather of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” credit also goes to Fats Domino for creating ska music. You can hear his influence clearly in the offbeat pacing of his 1959 track “Be My Guest,” which inspired Jamaican artists to experiment with new rhythms that would serve as the precursor to reggae music.

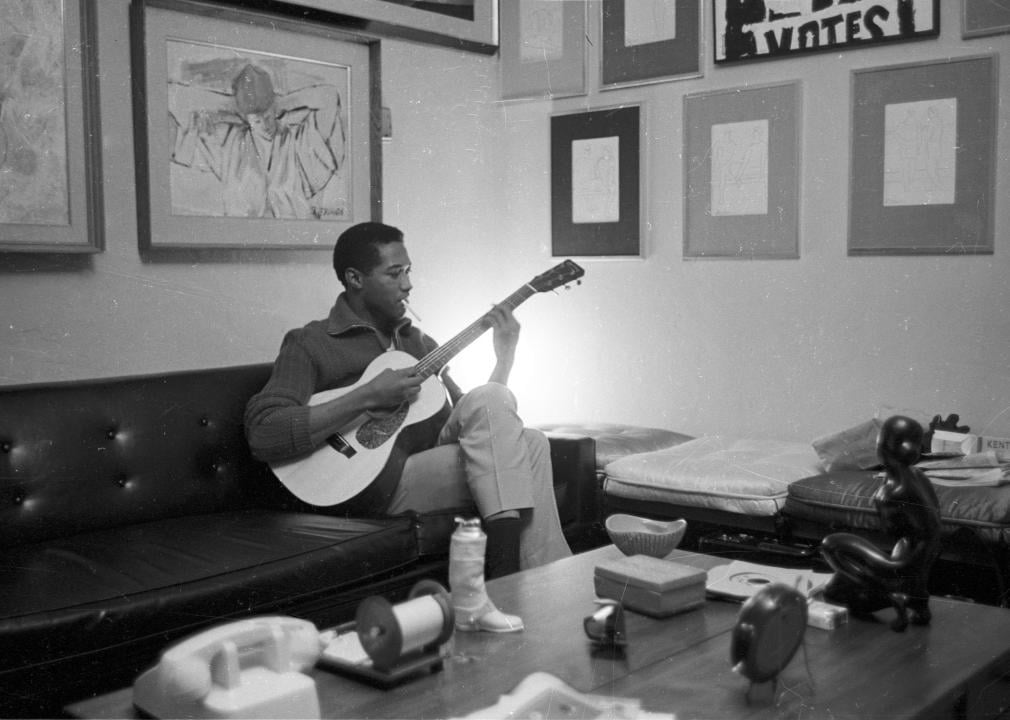

19. Sam Cooke

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “A Change Is Gonna Come” (1964)

– Who he inspired: Aretha Franklin, Al Green, Otis Redding, Rod Stewart, Stevie WonderUnlike Nina Simone, Sam Cooke struggled to find his place in the civil rights movement as he enjoyed a meteoric rise as a crossover sensation who bridged gospel and soul music with vanilla hits like “Bring It on Home to Me” and “Twistin’ the Night Away.” Something shifted for Cooke when he heard Bob Dylan’s 1963 protest song “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dissatisfied that white singers should be the only ones discussing civil rights, Cooke came out the following year with the emotional “A Change Is Gonna Come,” off his album “Ain’t That Good News.” It was his 13th—and final—album before he was shot and killed in a motel on Dec. 11, 1964.

20. Curtis Mayfield

Frans Schellekens // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Keep on Pushing” (The Impressions, 1964)

– Who he inspired: Tracy Chapman, Sly Stone, Stevie Wonder, Sinead O’Connor, Jimi Hendrix, Bob MarleyCurtis Mayfield goes down in history as one of the most politically conscious artists of his time, a talented songwriter and guitarist, progressive soul musician, and insightful record producer. Mayfield got his start in a gospel choir and joined The Impressions when he was just 14 years old. Impressions songs encouraged Black rights and Black power; and the band’s 1965 album “People Get Ready” was widely considered the soundtrack for the civil rights movement. His career spanned the next three decades, with his last recording (“New World Order”) in 1996.

21. Isley Brothers

Chris Ware // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Go for Your Guns” (1977)

– Who they inspired: The Beatles, Michael Jackson, Earth, Wind & Fire, Salt-n-Pepa, Kool & the Gang, Prince, Boyz II Men, Kendrick LamarThe Isley Brothers transformed themselves and modern music along the way from their start singing “The Cow Jumped Over the Moon” (1957) and “Shout” (1959), to “That Lady (Parts 1 & 2)” (1973), and “Go for Your Guns” (1977). The group picked up new members along their circuitous path through gospel, rock ‘n’ roll, Motown, civil rights icons, folk, and funk, including a young guitarist named Jimi Hendrix, who played with the band until 1965; and their wild, rollicking legacy from managed to inspired virtually everyone who came after. The group has been called, with absolute seriousness, the “most important American band of all time” for an influence rivaled only by the Beatles.

22. Diana Ross

Paul Natkin // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “I’m Coming Out” (1980)

– Who she inspired: Mary J. Blige, Beyoncé, Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Roberta Flack, Toni Braxton, Dusty Springfield, Mariah Carey, Michael JacksonDiana Ross and her mighty Supremes set the pacing for the Motown sound from the moment they formed in 1959 throughout the 1960s, with their voices as the soundtrack of the times. Ross’ departure from the band, in a move Beyoncé would echo decades later, would launch an even bigger, more influential musical career. Ross was one of the biggest female artists throughout quick musical changes of the 1970s and ‘80s and would inspire all Black women vocalists who came after, from Roberta Flack to Mary J. Blige.

23. Stevie Wonder

Michael Putland // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Sir Duke” (1976)

– Who he inspired: John Legend, Erykah Badu, D’Angelo, Kanye West, Michael Jackson, Lauryn Hill, PrinceStevie Wonder (born Stevland Hardaway Morris), blind since infancy, demonstrated an early mastery over multiple instruments and a natural singing ability. His first album came out in 1962 when he was just 12. Similarly to Curtis Mayfield, Wonder didn’t shy away from the systemic racism he faced every day: “Living for the City” confronted these issues head-on as early as 1975, when few other artists were doing so. Most critics agree Wonder’s crowning achievement was the 1976 album “Songs in the Key of Life,” a far-reaching, poignant album that earned the distinction of Album of the Year at the 19th Grammy Awards.

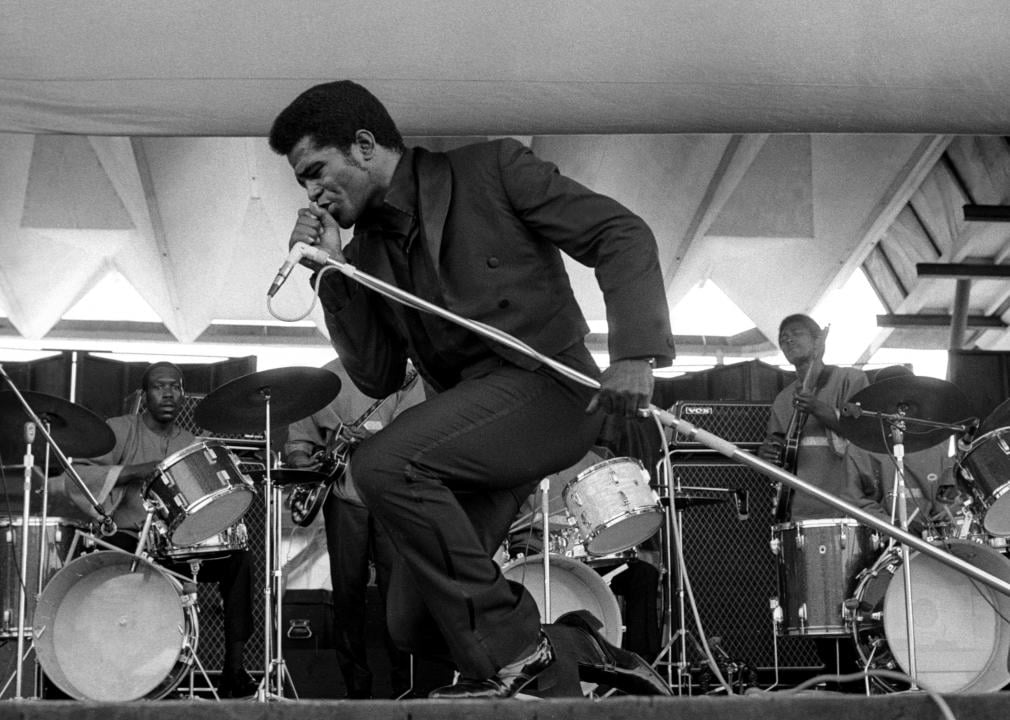

24. James Brown

Tom Copi // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Please, Please, Please” (1956)

– Who he inspired: Public Enemy, Michael Jackson, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Prince, Fela Kuti, Tina TurnerJames Brown’s first commercial recording, “Please, Please, Please,” has all the elements that made James Brown James Brown. The song has no lyrics beyond the title itself, with a few lines of longing (“Baby you did me wrong,” “Well, well you done me wrong,” and so forth), which would have been a tough sell for virtually any other artist.

Brown also brought out his cape bit for this tune when he performed it (a schtick that has to be seen to be truly appreciated), in which he runs himself ragged on stage until a cape is put over his shoulders and Brown is guided away—only for Brown to toss the cape off in dramatic fashion and return to the microphone. The scene thrilled audiences and was one he repeated throughout his decades-spanning career. And, perhaps most tellingly, record labels at first were so put off by the grittiness of the song when he began performing it in 1954 that Brown went unsigned until 1956 when King Records took a chance and set the Hardest Working Man in Show Business in motion and, arguably, changed soul music forever while setting the stage for a new genre of music called hip-hop.

25. Marvin Gay

Paul Natkin // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “What’s Goin’ On” (1971)

– Who he inspired: The Weeknd, Robin Thicke, The Rolling Stones, Alicia Keys, Outkast, Seal, Gnarls Barkley, The Band, Aretha Franklin, The Strokes, Diana RossSoul artist Marvin Gaye’s influence can be heard in modern-day tracks by Robin Thicke (“Blurred Lines”), The Weeknd (“The Music”), and Bilal (“Love It”). The talented musician did more than write his own tunes still adored today: He was also responsible for massive hits for The Marvelettes, Martha & The Vandellas, and did production work for Gladys Knight & The Pips and Chris Clark and the Originals. His 1971 album “What’s Going On” is widely understood to be one of the most transformative, important albums of the entire 20th century.

26. The Temptations

Michael Ochs Archives// Getty Images

– Essential listening: “My Girl” (1964)

– Who they inspired: The Jackson 5, Macy Gray, Al Green, The Pointer Sisters, The Doobie BrothersR&B megastars The Temptations were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1989 and were rated the #1 R&B/Hip-Hop Artists of All Time by Billboard Magazine. The Temptations’ influence over soul music and R&B has been compared to that of the Beatles over pop and rock, and their dance moves and singing inspired everyone after them from boy bands to solo acts.

27. John Coltrane

JP Jazz Archive // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “India” (1963)

– Who he inspired: Kendrick Lamar, Frank Zappa, Jimi Hendrix, The ByrdsHistory’s most important tenor saxophonist John Coltrane did more than turn jazz on its head: It created a whole new musical genre called psychedelic rock. The Byrds, who wrote “Eight Miles High”—widely regarded as the first psychedelic rock song—took a direct cue from Coltrane’s albums “Africa/Brass” and “Impressions,” specifically the track “India” from the latter.

28. Aretha Franklin

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I loved You)” (1967)

– Who she inspired: Jennifer Hudson, Luther Vandross, Chaka Khan, Whitney Houston, Amy WinehouseAnyone with a set of ears could have known in 1956 that 14-year-old Aretha Franklin was going to be a star when she was recorded live by J-V-B records singing “You Grow Closer” at New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit (the complete recordings were released in 1965 by Checker Recordings). Just six years later, she was laying down blues and big-band tracks like “Nobody Like You” that would set her inevitable ascendancy to a cultural icon with a seven-decade career spanning gospel, soul, R&B, pop, rock, and virtually everything in between. In 1987, she became the first woman inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

29. Jimi Hendrix

Evening Standard // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Little Wing” (1967)

– Who he inspired: Jeff Beck, Prince, John Mayer, Kirk Hammett, Isley BrothersJimi Hendrix grew up listening to Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters, and jazz music, all of which are audible in his early recordings. In addition to being one of the greatest guitar players to ever live, he was also one of the greatest performers. Hendrix was notorious for playing guitar with his teeth, setting instruments on fire, and smashing them on stage. He took chances with music no one had taken before and paved the way for future innovators like Prince.

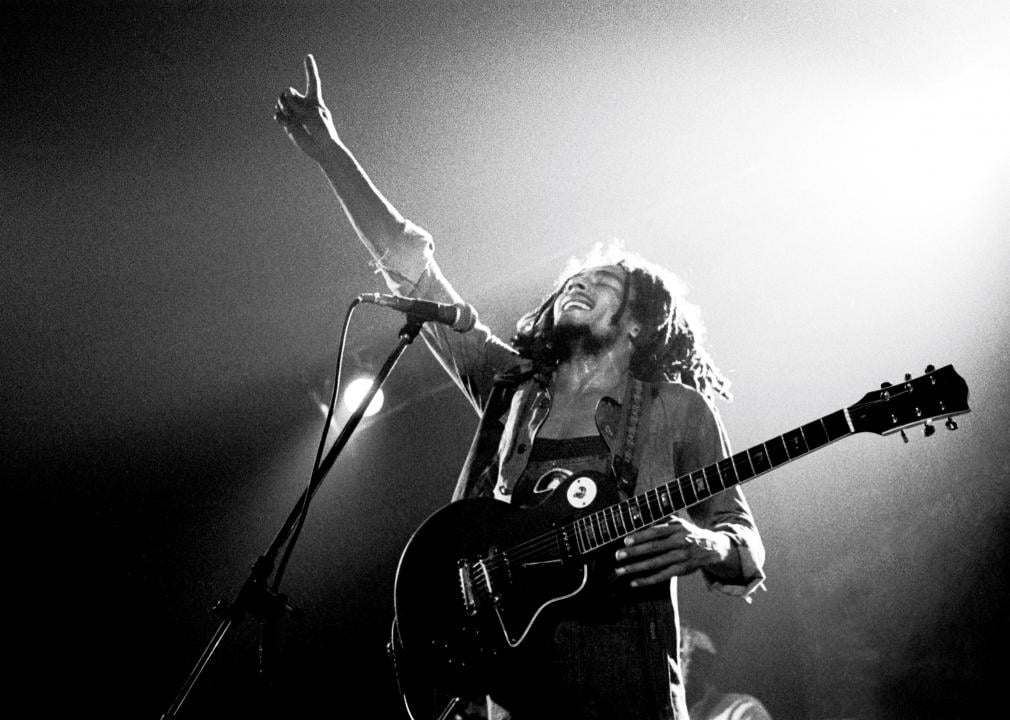

30. Bob Marley

Gijsbert Hanekroot // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Duppy Conqueror” (1971)

– Who he inspired: Immortal Technique, The Police, Zac Brown Band, Ziggy MarleyBob Marley sold more than 20 million records and goes down in history as being the first worldwide success to come from the “Third World.” As an ambassador for reggae music, he helped to spread Rastafari messaging through his songs and shone a spotlight on Jamaica and its politics. He additionally made reggae mainstream, paving the way for its international popularity throughout the United States, Britain, and Africa.

31. DJ Kool Herc

Jemal Countess // Getty Images

DJ Kool Herc was hosting a party in 1973 in the Bronx when he did something that had never been done before: a technique he called the “Merry-Go-Round.” To pull it off, he used two turntables to switch between breakbeats of James Brown’s “Give It Up Or Turn It Loose,” Michael Viner’s “Bongo Rock,” and Babe Ruth’s “The Mexican.” The result was modern-day hip-hop as we know it.

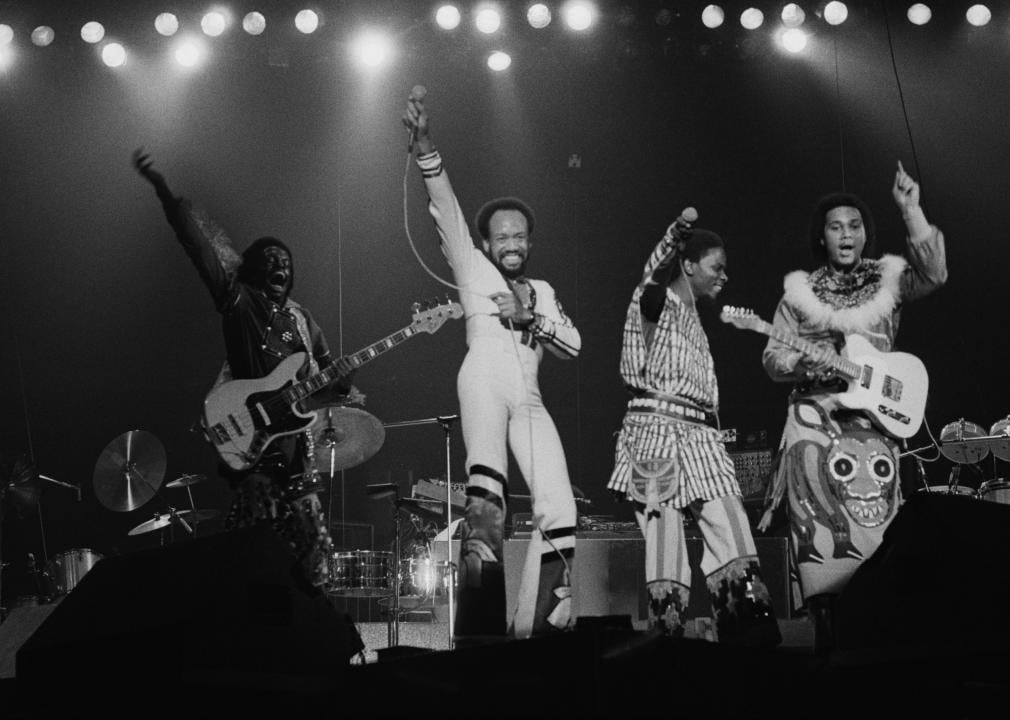

32. Earth, Wind & Fire

Michael Putland // Getty Images

– Original members: Maurice White (vocals, kalimba, drums, percussion), Verdine White (bass, percussion, vocals), Philip Bailey (vocals, conga, percussion, kalimba), Ralph Johnson (drums, percussion, vocals), B. David Whitworth (percussion, vocals), Myron McKinley (keyboards, musical director), John Paris (drums, vocals), Philip Bailey Jr. (vocals)

– Essential listening: “Sing a Song” (1975)

– Who they inspired: Beyoncé, Daft Punk, Rick James, Rihanna, Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, Outkast, Prince, Isaac Hayes, Curtis MayfieldEarth, Wind & Fire (EWF) stands alone as the biggest funk band ever, with tracks that shot to the top of the charts throughout the ‘70s. The group was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2000, earned six Grammys, and sold more than 90 million albums just in the United States. EWF stayed ahead of the times, incorporating disco, funk, jazz, doo-wop, soul, Latin, and pop into their tracks over the years. Additional evidence of the band’s lasting legacy is apparent in how many artists borrow EWF tracks: Everyone from Public Enemy to LL Cool J have sampled tunes from the band’s staggering catalog.

33. Millie Jackson

David Corio // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “If You’re Not Back in Love by Monday” (1977)

– Who she inspired: Lil’ Kim, Macy GrayMillie Jackson pushed the envelope for powerful women songwriters with her for her unapologetic sexuality, occasional raunchiness, and penchant for being provocative. She wasn’t afraid of racy album titles (see 1977’s “Feelin’ Bitchy”), is known as “the queen of raunchy soul,” and was described by the Washington Post in 1986 as “a veteran virtuoso of vulgarity.” Jackson initially drew inspiration from singers like Gladys Knight but soon went her own way, defining herself by coloring outside the lines of what was deemed acceptable out of women artists at the time. She was also among the first woman R&B artist to write songs about cheating from the cheater’s perspective—unheard of at the time.

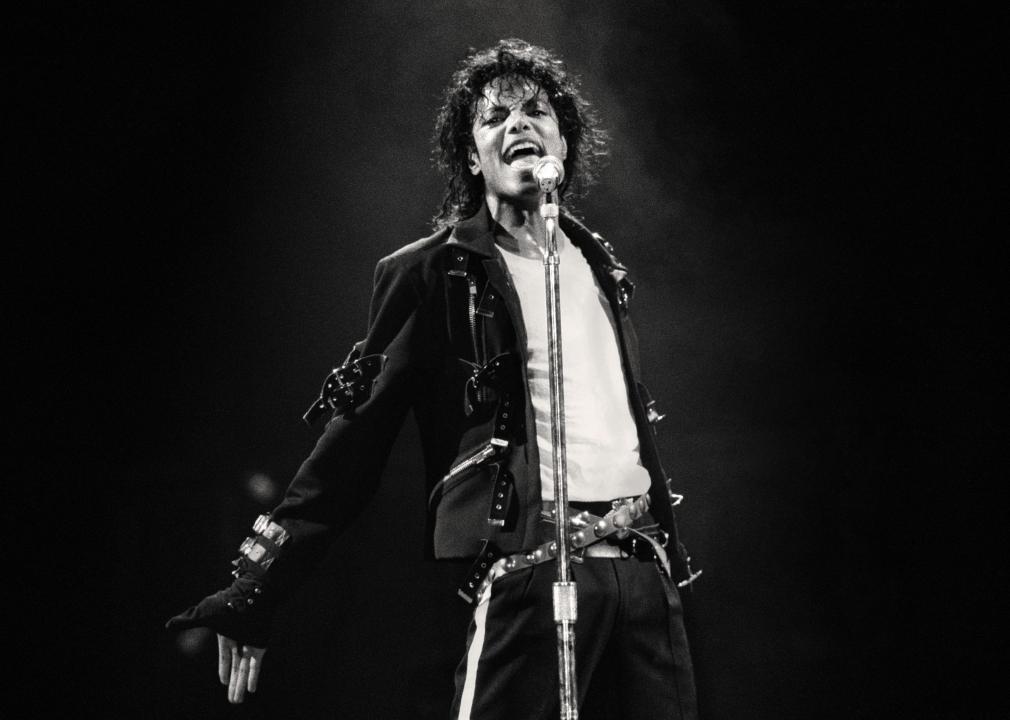

34. Michael Jackson

KMazur // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Thriller” (1982)

– Who he inspired: Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, Bruno MarsMichael Jackson’s conflicted history can make it difficult or unseemly to appreciate the irreversible impact he had on today’s music. In his musical career, Jackson broke the color barrier by being the first Black artist on MTV with his “Billie Jean” video; he determined a new method of production and promotion with “Thriller;” and he took home hundreds of awards. He also followed in the footsteps of greats like Nat King Cole, pushing the boundaries of what roles Black men could acceptably occupy in American society, whether adored, wanted, or rebellious.

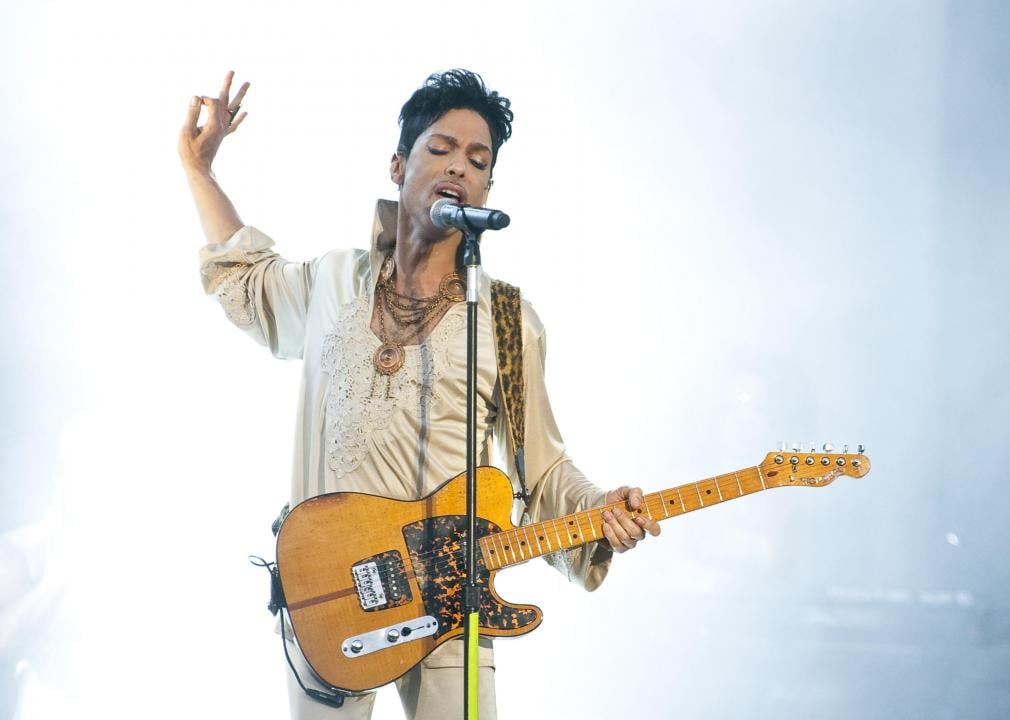

35. Prince

Neil Lupin // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Purple Rain” (1984)

– Who he inspired: D’Angelo, Beyoncé, Frank Ocean, Sinead O’Connor, Justin Timberlake, Beck, Rihanna, Janelle MonáePrince’s musical experimentation transformed rock, funk, pop, and new wave music. He was 7 when he wrote his first song, “Funk Machine,” and used not just his solo career to impact how music was packaged and received, but his work as a collaborator and producer. Early in his career, some of his most ambitious works like “777-9311” were used in other groups like The Time, in which Prince sang backing vocals and played all the instruments. No one had heard anything like Prince before he came along—but forever after, you could hear his legacy in tunes from acts as wide-ranging as Beck and Justin Timberlake.

36. Chuck D. // Public Enemy

David Corio // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “ Fight the Power” (1987)

– Who he inspired: Mos Def, Tribe Called QuestChuck D.—prolific producer, activist, and rapper—once famously called Public Enemy, the rap group he formed, the “CNN for Black people.” That’s because in the late ‘80s, the masses had to look to hip-hop to cover racial disparities in American culture, the prison-industrial complex, poverty, profiling, and police brutality. Chuck D. helped to strengthen a culture of hip-hop that worked for social change and inspired a generation of artists.

37. Janet Jackson

Christopher Polk // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “ Rhythm Nation” (1989)

– Who she inspired: Brandy, Beyoncé, Rihanna, Mariah Carey, Spice Girls, John Legend, Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Justin Timberlake, Black KeysJanet Jackson hit her peak alongside fellow heavyweights Whitney Houston, Madonna, and Tina Turner, but managed nevertheless to carve out her own highly specific role in American music that would be forever imitated yet never duplicated. She was able to reach listeners of all races and backgrounds and every age group, has sold more than 100 million records, and won dozens of accolades from Grammys to American Music awards.

Her 1989 album “Rhythm Nation” stands as one of the most significant of its era, with its title track described by Jackson herself as “the national anthem for the ‘90s.” From political messaging and stunning dance routines to her ability to transcend genres (techno-soul-rock-pop and back again), Jackson set new standards for music videos, dance choreography, and breaking sexual taboos. Her legacy continues to reverberate throughout musical genres as far-flung as indie rock and R&B.

38. Tupac Shakur

Al Pereira // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Dear Mama” (1995)

– Who he inspired: Kendrick Lamar, Janet Jackson, Eminem, Justin Bieber, DrakeTupac Shakur was the first hip-hop artist to record a double album and, in 2017, he posthumously became the first solo rapper to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. He is revered as one of the most influential rappers in American history and left his indelible mark on American culture not just as a rapper with 11 platinum-selling albums and worldwide notoriety, but also as a poet.

39. Jay-Z

Brian Ach // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “Public Service Announcement” (2003)

– Who he inspired: Kendrick Lamar, Kanye WestThe stunning, award-speckled rise of Jay-Z (Shawn Carter) over his decades-long career began with his independently released “Reasonable Doubt” in 1996 on his newly created label, Roc-A-Fella, and continues to this day with that label making him the richest man in hip-hop. His net worth stands at around $1.4 billion, according to Forbes, which makes him the first hip-hop billionaire in history. He demonstrates the vast reaches of today’s music industry, with his hands over the years in a streaming service, alcohol company, clothing line, sports club, and various entertainment labels. His secret? Relying on himself to build his brands and rapping about that which he knows most about: himself. It’s not a stretch to say he’s believed to be among the best (if not the best) rappers in history, who can have fun while delivering poignant observations and difficult truths.

40. Beyoncé

Larry Busacca/PW18 // Getty Images

– Essential listening: “ Formation” (2016)

– Who she inspired: Ariana Grande, Sam Smith, Nicki Minaj, Lady GagaBeyoncé got her start as a teenager in Destiny’s Child, which in its own right was one of the best-selling girl groups in American history. She forged out on her own with “Dangerously in Love” in 2003. As her success grew so too did her messaging, which culminated in 2016 with the epic “Lemonade,” her sixth studio album. That record, which explores themes of family history, politics, relationships, and infidelity, came alongside an hour-long art film.

41. Kendrick Lamar

Santiago Bluguermann // Getty Images

Rapper Kendrick Lamar became the first rap artist to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2018 for his fourth studio album, “DAMN.” At just 34 years old, Lamar has already earned 13 Grammys and a nod from Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. He is widely considered one of his generation’s most influential rappers, and as a songwriter and producer, he’s already helped to churn out and develop new talent, from Ab-Soul to Sza.